Slim School

Stat Lux In Monte

"Upon the hill top stands a guiding light"

![]()

Photos and Memories

of

Major William Harrison and Betty Harrison.

![]()

I would like to thank Willie Harrison the son of Major William (Bill) Harrison and Betty Harrison for making available the documents and photos on this web page and also thank Katie Crammen sister of Willie Harrison for her assistance in compiling the following documents.

![]()

How it all began.

Major William (Bill) Harrison was the first headmaster of Slim school and was instrumental in its inception with Mrs Betty Harrison who became the school Headmistress.

Bill

and Betty Harrison 1951

Below is Major

Bill Harrison's memoir of how the school came into being.

Unfortunately due to the passage of time this is all that is left of the

original document.

Below is a

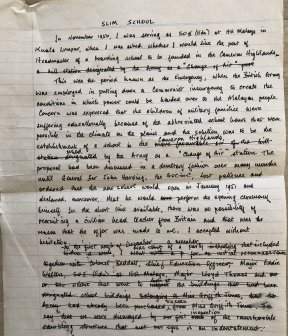

transcript of the original document above. Slim

School In

November 1950, I was serving as SOIII (Education) at HQ Malaya in Kuala Lumpur,

when I was asked whether I would like the post of Headmaster of a boarding

school to be founded in the Cameron Highlands. This

was the period known as the Emergency, where the British Army was deployed in

putting down a communist insurgency, to create the conditions in which power

could be handed over to the Malayan people. Concern was expressed that the

children of military families were suffering educationally because of the

abbreviated school hours that were possible in the climate on the plains and the

solution was to be the establishment of a school in the Cameron Highlands used

by the Army as a “Change of Air Station”. The proposal had been discussed in

a desultory fashion over many months until General Sir John Harding, the General

Officer in Charge lost patience and ordered that the new school would be open in

January 1951 and declared, moreover, that he would perform the opening ceremony

himself. In the short time available, there was no possibility of recruiting a

civilian head teacher from Britain and that was the reason that the offer was

made to me. I accepted without hesitation. In

the first week of December, I was a member of the party that included Colonel

Bedall, Majors Eddie Walters, Lloyd Thomas, John Kane and one or two others,

sent for a first look at the school buildings that had already been purchased,

unseen, from Miss Griffith-Jones, with the aim of determining what work would be

needed to convert them for our purpose. To say that we were dismayed by the

sight of the ramshackle structure that met our eyes is an understatement. It was

decided that because of the short time available before General Harding was to

come, the work would be undertaken in two phases. Phase One, to be completed by

January, would make the buildings acceptable for the GOC’s official opening.

Work on Phase Two would begin immediately after. The words “Phase Two”

became a joke among my civilian colleagues thereafter because, over the next

three years of my tenure of the post, not one brick was laid. Once the staff

officers had satisfied the General that the school was launched, they felt free

to turn their attention to more pressing matters. The

first few weeks before the children arrived in January were a nightmare. Not

only did the buildings have to be gutted but furniture and equipment was

delivered in profusion while there was nowhere to store it. Soon, the first

members of staff arrived, Isabel Onion and Eve Pringle. They were joined by

Warrant Officer Coward and Sergeant John Fiddler. Bill

Harrison Headmaster,

Slim School 1950 - 53 Webmaster's

note: Unfortunately

due to the passage of time the remainder of the above document has been lost. Below is

copy of Betty Harrison's Memoir of how the school came into being.. (This document was written in

about 2010 whilst Betty Harrison was studying for her 3rd degree). Below is a transcript of the

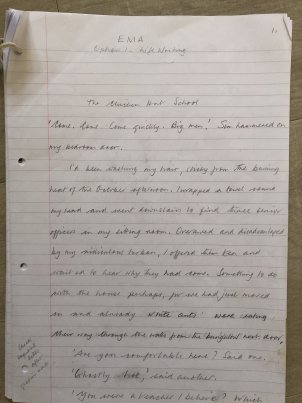

original document above. The

Chicken Hut School (As

remembered by Betty Harrison) Come!

Come! Come quickly. Big men! Sim hammered on my bedroom door. I'd been washing

my hair, sticky from the burning heat of the October afternoon. I wrapped a

towel round my head and went downstairs, to find 3 senior officers in my sitting

room. Overawed and disadvantaged by my ridiculous turban, I offered them tea and

waited to hear why they had come. Something to do with the house perhaps, for we

had just moved in and already white ants were eating their way through the walls

from the bungalow next door. “Are

you comfortable here?” said one. “Ghastly hot.” said another. “You were

a teacher I believe? Which University?” drawled the Brigadier. “Cambridge

man myself.” I

was new to army life and understood little of its protocol, other than that it

was a man's world where it was wise to watch and listen. Bookish women did not

go down well. I was wary. Light

began to dawn. Cambridge? Was this the Chief Education Officer from Singapore,

who was said to have once got on the wrong train in Peterborough, and finding

himself stranded in Cambridge, thereafter claimed that city as his alma mater?

It was rumoured that he was the natural son of a former monarch, who had endowed

him with a rank he had not earned. Lately, the word was that he was being

harried by the General, a real soldier, about the proposal for a secondary

school in the cool climate of the hills, where a full day could be worked. The

plans were supposed to be well advanced but so far existed only in the

Brigadier's imagination and a pass-the-parcel file moving from desk to civil

service desk. The scheme sounded like hard work and it would cost money. “Splendid.”

said the General “Let's have the opening ceremony in January then. Nineteenth

suit you? We'll settle the details before the Christmas break” “Sir!”

said the Brigadier, an emperor about to lose his clothes, red tabs and all.

Having satisfied themselves that I could speak the King’s English, and had no

children, my visitors left, hurrying away from bandit country over the Causeway

back to Singapore. This was 1950 and Malaya was at war. The Japanese had left

four years earlier but now there was a different enemy engaged in a last

ditch attempt to take the Peninsula for Communist China. Rattling

over the potholes, the staff car was hot and smelled of feet and the driver’s

patchouli hair oil. The Brigadier was tetchy. How had he landed up in this

God-awful place waiting to be shot at? “No

time to recruit in England.” he said. “She'll have to do. Harrison can be

headmaster and she can teach. Two for the price of one. Keep the costs down.” “Yes,

but where?” said the Colonel. “Wasn't

there a boarding school in the Camerons?” “It

closed before the war, Sir. It's been empty for 10 years.” “Buy

it,” said the Command Secretary. “Send the engineers up. Give it a lick of

paint. Furniture. Say for a hundred. Call it Phase One. Start a file for Phase

Two - work we can leave until later.” Much later, he thought. Not before I go

back to England. “It's

a school, Sir. Won't they need books?” the Captain cleared his throat timidly. “Books?

What sort of books? Oh well, yes I suppose so. Whatever we can find here.,”

said the Brigadier. “They’ll have to manage until we can get some shipped

out. Six months at least. I've got an old Gestetner they can have. Improvise.

They'll have to improvise.” “Er,

they Sir? Who Sir?” “Oh

for God’s sake man. Just get on with it.” The Brigadier's gin

sling was waiting for him at the Club. “We've got two teachers. Find some

more. There will be a few graduates in the primary schools and among the

Education Corps sergeants. It's got to look like a proper school when Harding

goes up to open it. We've got six weeks.” After that they're on their own, he

thought. It's four hundred miles from Singapore. The

school turned out to be a collection of near derelict wooden buildings, and the

lick of paint was a wholesale gutting and re-roofing, with new kitchens and

bathrooms and a central hall. “Bloody

chicken huts” said the Sapper Major. By

early December we were four thousand feet up in the Highlands where the cool air

was compensation for the chaos all around us. Sim Yap Seang and his family came

with us to take charge of catering and he recruited two young brothers Wong and

Wah, with wide moon-washed faces, from a nearby Kampong to help in the kitchen.

Other locals turned up looking for jobs. There was Violet, a convent girl, whom

Reverend Mother had married off to an elderly Indian husband to avoid worse

things when the Japanese were advancing. There was Jane, who had been left

behind by a Dutch family at the same time. She had been their servant, perhaps

slave, brought from Africa. “My mother done gone finish” she says. “I

stay.” She stationed herself outside the headmaster’s office, coming to tell

me who had gone in there, especially if they were female. “What that matron in

there long time no come out?” she says, and I suppose that the Dutch Twan's

roving eye had called for such surveillance. Matron,

sent up from Singapore, was a tall Anglo-Indian lady, impressively bosomed and

of commanding presence. “I was housekeeper to Lord Millearn at Government

House before he went back to Youkay”, Mrs Playfair announced. She did not see

herself dispensing pills or sticking plasters on grubby knees, nor did she

approve of the lack of hierarchy. We were a diverse community, a mixture of

races, roles and ranks, where from the beginning what everyone contributed was

valued and respected. Two army sergeants, a musician and a geographer turned up

and one by one, civilian teachers plucked from the jobs they had come out to do,

began to arrive. Up there on the hilltop, we set about making a school, a little

oasis of how things ought to be. Out there on three sides, there was thick

jungle, hiding place for a dwindling guerrilla army of desperate men. The

British had come back to help in the rebuilding of a plundered economy and to

support the civil power towards independence, Merdeka, when Malaya would become

Malaysia. The bandits were not yet ready to acknowledge that theirs was a lost

cause. It

is January 1951 and in less than two months we have created classrooms and

teaching materials. Fed with oozing black ink, the Gestetner has been busy. We

have scrubbed floors, set out beds, lockers, desks and chairs. Now we are labeling

places in the dining hall. Tomorrow we must look as if we have been

here forever, for the children must believe that we can keep them safe, that we

know what we are doing. None of which is true. The adventure has begun. Our

chapter in a forgotten war. I

am sitting in my orange chair in the late afternoon, waiting for the rumble of

armoured vehicles climbing from the village past the scarlet flame trees and the

rock wall hung with glistening pitcher plants, purple and green in the sunlight.

The memory is like an old photograph, fading at the edges, but the centre is as

sharp as if the Box Brownie had taken it yesterday. The black and white dog who

has recently moved in, is sitting at my feet and she hears the noise first.

There is a squeak of brakes and the clang of metal doors and I am outside with

David, Bill, John, Eve and everyone who has come running to catch the moment. A

sweaty tangle of twelve and thirteen year olds, blinking at the light, spills

from the darkness of the iron “coffins”. “Hello Miss,” says Edmund*, all

big teeth and pebble glasses. “This is my friend Derek* and his brother

Stuart*.

They are twins, and this is Brenda* and Edith*. And Miss, where's the toilet? I'm

bursting.” I

see them still in my mind’s eye, bemused pale ghosts from the past, crumpled

and anxious. Even the twins, identical Just Williams, are too tired to be

hatching any of their little ruses for the moment. Born during the blitz, their

soldier fathers seldom at home, these children have come out on troopships to

army camps where many have been taught to use guns because nowhere is safe,

though we pretend it is. Some have been traveling for two days from Johore,

past rice fields, rubber plantations and pineapple groves, glimpsed now and then

through the thick grey smoke of the old steam train, wheezing its way north on

its single track. Some have come in trucks under armed guard with planes roaring

above to scout for dangers ahead. They have lain on oily floors when the wagons

have driven through terrorist strongholds, and it has been hot, steaming hot,

until at last they have come together at Tapah to travel in convoy up the

mountain and to the Cameron Highlands. Five more hours and they will be there.

The winding road curls into horseshoe bends cut through high cliffs where wild

orchids and trumpet vines tumble down the rocks, and where an ambush always

threatens. How

will these children sleep tonight in their new beds, under blankets instead of

mosquito nets, the whirr of ceiling fans replaced by the rattle of rain on the

tin roofs and the tick-tocking of the nightjar from his tree by the kitchen?

Edmond dreams of the dead bandit he saw being brought out of the jungle, slung

on a pole because the paths are narrow and because the villagers must see that

the man who killed their children when he was refused money has been caught. We

are up at seven, eating breakfast at eight and in assembly at nine. There are

lessons all morning, games in the afternoon, prep and clubs in the evening, a

conventional structure for an unconventional school. We teach without books, out

of what we know, and somehow between us we can cover the curriculum. We share

our enthusiasm for fencing, country dancing, drama and singing. Soon there will

be a school farm with pocket money shares in pigs and hens housed in the old

stables. It is a world without television, computers and mobile phones and we

must entertain ourselves. The Art Room is always open, where David, his white

coat stiff with paint, nurtures talent by encouragement, amid a chaos of paper,

paint jars and empty coffee cups. He invents nicknames, sometimes scurrilous,

and the children love him for it. He is friends with John, the musician who is

making a programme for the opening ceremony, peering at his score through army

issue, steel rimmed glasses. His civilian clothes seem to have been dug from the

bottom of a musty kit bag. Where he has come from, this unlikely soldier, to

pour such music from his stubby fingers? David is suggesting hymns and John

crashes out “For All the Saints”, and they roar the words, shouting with

delight at the noise they are making. Eve, good girl guide, is teaching some

children a sword dance, and Alan is setting up an exhibition boxing match

between Kulraj and Jagindra, the youngest of our six Gurkha boys. Thin arms and

big gloves flailing, they launch mighty blows and miss each other, toppling over

in a giggling heap. We

are preparing for the big day. We are improvising. Two weeks into the term and

we are ready for the little General, hero of the Italian campaign, when he comes

to open the school. He tours the classrooms and the dormitories, firing

questions at the Brigadier and striding ahead before he can answer. The children

are waiting in the hall, pretending to be a real school in their white shirts

and red ties. The visiting party pauses outside to look across at the old hill

station, still with its golf course and scatter of leave bungalows. There is the

Smokehouse, mock Tudor country house, set in its garden of English roses, where

the hosts regaled their guests with stories of Changi, where they were both

interned. Violet is hovering by the hybiscus hedge in her best sari, sweet

jasmine wound into her long black plait. She is wafting a straw brush with a

sweeping backhand to look as if she is working. Jane, self-appointed bodyguard

to the Headmaster, stands a few feet behind him rocking back and forth, on

spread bare feet. She is ecstatic when General Sir John Harding shakes her hand,

though her other hand flies up to her mouth to cover a near toothless grin. The

ceremony in the Hall is brief. The General expresses his pleasure at being asked

to open the school, though he has invited himself. He announces that the school

is to be called after Field Marshall Sir William Slim who has sent his good

wishes from Australia where he is now Governor General. Not to be outdone, the

Brigadier rises to his feet. “This day, the 19th of January 1951, this day

will henceforth be known as Founders Day.” He hears himself rallying the

troops at Agincourt. “It will be celebrated every year by a half holiday and

I'm pleased to tell you that I have approved a design for a school crest, which

will bear the motto: ‘Stat Lux in Monte’. I'm sure you will agree with me”

he says to the sea of blank faces, “that it is a most appropriate phrase.” The

children applauded enthusiastically, though they have no more idea than he has

what the Latin words mean. That

night the lights are on all around the perimeter fence, because we were under

siege. The Malay guards have disappeared and are replaced by Gordon Highlanders,

ready for a fight. We are woken by gunfire and must rouse the children and crawl

to the safety of the hall where there are no windows. We lie on the floor until

the shooting stops and the guard commander gives us the all clear. School starts

at nine as usual next morning and the children are reassured that the guards

have been firing at lights seen in the jungle west of the school, possibly glow

worms rather than bandits. The Headmaster is getting on with his history lesson

when a truck delivering rations backfires in the playground outside. Lizzie

Twigger, crisp little ginger plaits shaking with suppressed laughter, puts her

hand up. “Yes Lizzie?” “Glow worms, Sir?” she says. Most

of us will be at Slim School for the next three years and then our places will

be taken by other teachers and other children until the terrorists are defeated

and the Emergency is over. Peace will come, and independence safely achieved,

the soldiers and their families will go home. A lifetime later, the children

will find each other again and we shall meet and remember how it once was.

Astonishingly, they will say that of all their school experiences elsewhere,

those in the Chicken Hut School were the best. When it closed in 1964 Field

Marshall Slim wrote: “The

school lives on in all those boys and girls who have passed through it into the

world. Schools are like men. It is not important how they live but what they do

with the years that are granted and Slim School has achieved a great deal.” Betty

Harrison Slim

School 1950 to 1953. Addendum: Whilst Betty

Harrison was officially designated Headmistress this in fact was a full time

unpaid position. As mentioned in Betty's memoir a typical military solution of

"two for the price of one". This voluntary service was the beginning

of a pattern of voluntary service which interleaved her paid work throughout her

life. Amongst other things she founded and worked for The York Women's Counselling

Service (Go to this link to read a tribute to Betty) Betty had retrained as a psychotherapist when she reached mandatory retirement

age from teaching. She had incredible energy and was still working two weeks

before she died at the age of 87. *Webmaster Notes: I believe the twins

Derek and Stuart are the Walker twins. Edmond is Edmond

Hammond. Brenda is Brenda Baldwin Edith is Edith Peacock Bill

and Betty Harrisons Photos from Slim 1950 to 1953. 5 General Harding at Slim January 1951. 7 Staff and Pupils January 1951. 10 Group of Pupils. Need names please. 11 Mr Sim Yap Seang Catering Manager 1951 to 1964 13 The Harrisons with the Sultan of Pehang 14 Bill and

Betty Harrison at play. 15 Bill and

Betty Harrison at Smoke House. 16

Certificate of appreciation presented to Bill Harrison on leaving Slim School.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

An interesting aside regarding the above certificate. Out of the blue in March of 2014 I received an email from a couple living in Robin Hood's Bay in the North Yorks Moors National Park who had bought a cottage from Bill and Betty Harrison.

They had been up in the attic having a clear out and found the certificate. It had lain undisturbed for over 30 YEARS before being discovered! I put them in touch with Katie Harrison, Bill and Betty's daughter and the certificate returned to the family after it's long hiatus. That's serendipity.

![]()

© 1997 - Present. All articles & photos on this website are copyright and are not

to be published without permission.